Breathe

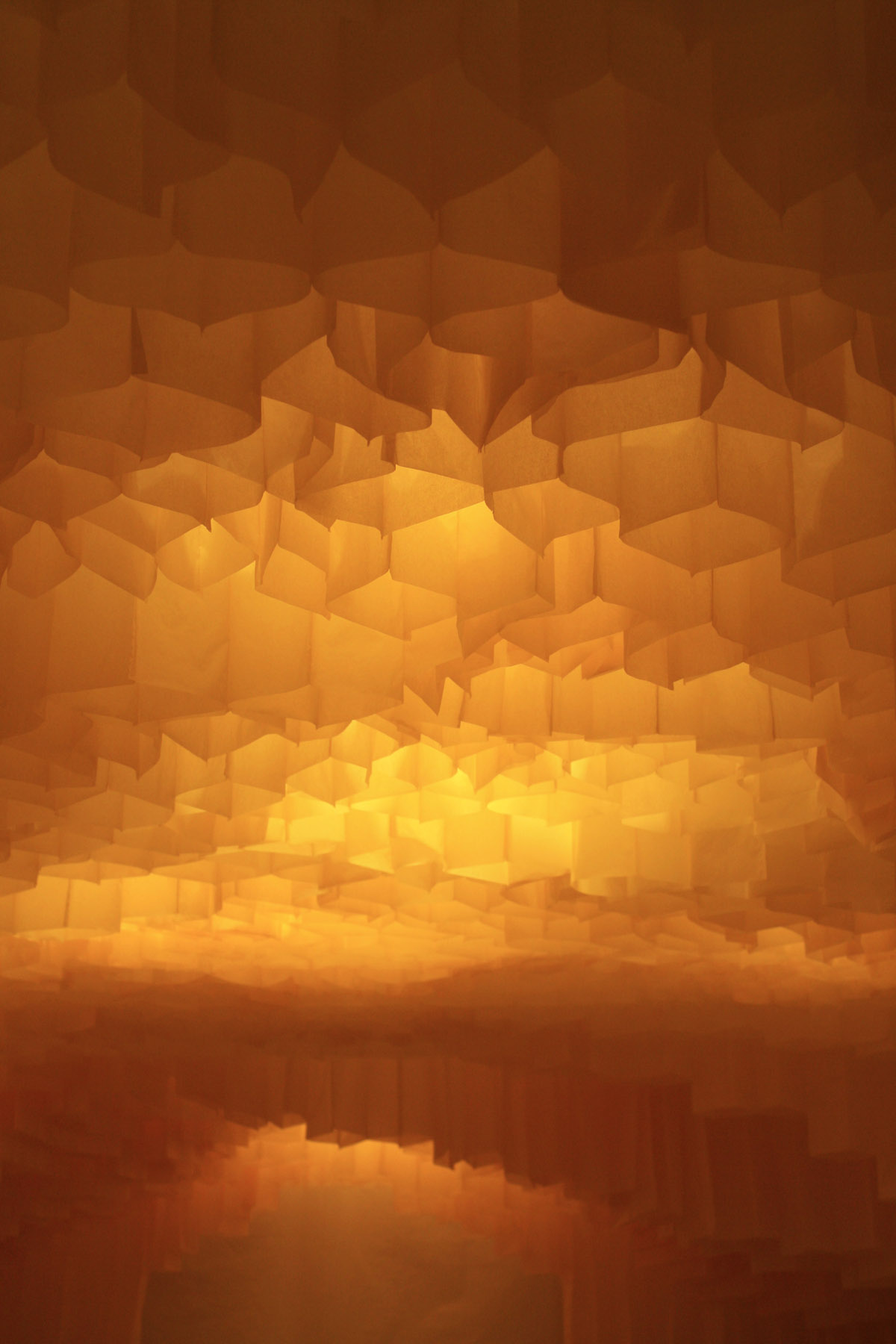

Viewers enter this installation under a cut paper canopy that is like an inverted honeycomb. Delicate drypoint images of swarms hover slightly away from the walls. Visitors participate by inflating handmade flat paper boxes with exhaled breath, inserting written wishes, and tying these to the ends of strings hanging from the ceiling. Over the course of the exhibition, there is an accumulation of boxes in and around the golden canopy that visually and figuratively represent a collective social breath.

Each new iteration of Breathe: the Emergent Colony was shaped by site and collaborators in its host city. When I conceived of the project in 2011, I was new to participatory and collaborative art. My design sprung from conversations about emergent colonies with my ecologist and bee keeper sister Sara Scanga, readings into the theory of evolution and the concept of superorganisms, and research into bees, swarms, and bee colonies. Working with musicians, a choreographer and dancer, a poet, and a chef I imagined that our work under the golden canopy would offer a deliberate exploration of what a utopian model of creativity might look and feel like in physical space.

Originally, I intended to create an opportunity for a collective imagined experience, something that would transcend an individual, private experience of visual culture and art. Today this is everywhere in the art world, but back in 2011 this was a new and hopeful concept to me. The first time I installed the piece (St. Louis, 2011) I heard from the gallery staff that people kept “doing things” in it. They would make impromptu dances, sing, hug each other for a long time, or applaud, for example. Religious leaders in the community asked to hold services in it, and a couple even asked if they could get married in it. In response to this experience, for the project’s second iteration (Kansas City, 2012) PLUG Projects helped me formally invite other makers in the community to collaborate within the space. In Kansas City, the composer Simon Fink and choreographer/dancer Jane Gotch invented a performance for the piece that blew away the show’s packed audience. Craig Howard, a masterly chef, invented honey candies for the exhibit, and the renowned poet Hadara Bar-Nadav contributed poems. At KMOCA in Kingston, New York, Jeremy Robinson created sound art to fill the installation. Bee colonies are described as “superorganisms.” The definition of a superorganism is: an organized society (as of a social insect) that functions as an organic whole. Evolutionary biologists have found that individuals within superorganisms genetically select based on the values of the superorganism rather than the individual. So, for example, when bees make decisions about where to position a new hive or which larvae should one day become the colony’s new queen, they collectively act for the betterment of the colony’s state. Some evolutionists have been thinking about how Darwin’s theory and the idea of the superorganism could apply to the functioning of human cities and communities, specifically how people select for the benefit of the group’s survival rather than their individual prosperities. I viewed this project as a chance to make a collective experiment related to how we function and evolve as a group within a golden, delicate, enveloping environment.

Excerpt from Take a Deep Breath, Dickson Beall, West End Word

Scanga told me that, while doing a residency in Andalusia, Spain, she visited cathedrals and noticed how the embellished ceilings in that architecture direct attention upward. She became interested in what happens in our bodies when we lift up our eyes and our hearts, and we intake a deep breath. She felt that the act of looking up opens our hearts and stretches the ligaments around the heart. She came to realize that an inhalation actually has a spiritual content to it. This involuntary thing that we do, all the time and every day, can actually be a vessel for spiritual content in our lives.

While Scanga speaks of spirituality, it is a spirituality that she says is all about relationships. In the world of conceptual art, the best artists are trying to make a difference and create an experience for the viewer, one that will be transformative in some way. Scanga is to be commended for doing that well.

As staging ground for an event called exhale, hundreds of paper envelopes, which were inflated by previous gallery visitors, remain as part of the installation. This is the second component to the show — the participatory part — where the visitor can write a wish on a slip of paper, which goes inside the envelope. Then the visitor inflates the envelope with one deep breath, and therein is the title exhale. The capacity of the envelopes is one single belly breath. These three-dimensional paper forms capture air from inside the body. What was invisible becomes an observable mass. The viewer/participant stays in the present, yet is simultaneously carried into the future, by the exhaled and captured breath in the envelope, which is added to the installation. By grouping the envelopes under the vaulted canopy, Scanga creates a shared experience.

Excerpt from CARRIE SCANGA: BREATHE, Nancy Newman-Rice, St. Louis Craft Alliance catalog essay

Carrie Scanga’s installation, Breathe, invites the viewer to not only experience the work as architecture, but also participate in its construction through related purposeful activities.

Breathe is a sacred space with vaulted ceiling comprised of delicate saffron colored tracing paper modules that are box-like in shape and form a gently arching translucent overhead honeycomb. The sacred space allusion as well as the honeycomb reference is further enhanced by the addition of several prints comprised of saffron ink on white translucent paper that suggest swarms of bees. The prints hang in natural alcoves formed as her vaulted ceiling slope to meet the wall and they seem an appropriate substitution for devotional icons.

Scanga’s construction, although arched, cannot be mistaken for the soaring arches one see in cathedrals or mosques. Instead, her arched ceiling forms a low protective canopy, more reminiscent of the catacombs under cathedrals. Strategically placed lights work with the ambient light to produce an otherworldly glow that further envelopes the viewer/participant. Scanga suggests that as we look up, we naturally inhale.

In order to exhale, the artist encourages the viewer’s full participation in another component of this project outside the confines of the structure. Using deflated origami envelopes folded from the familiar saffron colored tracing paper, Scanga has requested each viewer to write a wish on a piece of tracing paper, twist it into rope shape, inflate the envelop with a gentle exhalation, and finally use the twisted wish as a hook to be attached to fishing line that she has affixed to an overhead structure. The most interesting aspect of this project is the height at which each participant has tied an envelope; some are almost all at the same height, while another grouping, reflecting more idiosyncratic personalities at work, has tied the envelopes at various heights. The air currents in the gallery combined with the spontaneous movements of viewers, cause the suspended envelops to hover together like an agitated swarm of bees.

The process of inflating the envelopes and incorporating wishes adds an essential element of ritual to the sacred space. Precedents in the Jewish tradition include wedging pieces of paper containing prayers in the chinks of the Wailing Wall, or in the Catholic Church, where parishioners write the names of the deceased in a book during the month of November so that they may be remembered in prayers. That Scanga intended ritual to be the basis for this participatory act is an assumption; but it is undeniable that a wish can also be regarded as a prayer.